Remembering my dear father-in-law one year after he died. We are sad, but we are blessed by our memories of his contributions to others.My father-in-law, John W. Hall, MD, was very important to me throughout my adult life. His zest for life was inspiring, and he always took many willing participants along on his adventures. He was important to so many people in so many realms. To us as Dad, Grandpa, Husband, and Uncle, to his sailing friends as Skipper, and to his patients as Doc, a urologist who led and pioneered throughout his career. He never retired, wanting to continue to serve others throughout his life.

I often wish to share a conversation with Dad, and especially during the past weeks of the Russian war on the people of Ukraine, I wonder what he would be thinking. So, in honor of the people of Ukraine, I share with you an excerpt from Dad's memoir, "I'd Rather Be Sailing," in which he describes the two medical mission trips he made to Ukraine in 2002 and 2003-2004. Ukraine 2002 Rev. David Behling started Airo Ministries as the organization to support his mission trips. He took trips to Russia, Jamaica, and Central America before we joined him for a trip. He had been denied a return trip to Russia when the Russian government prohibited any religious group except the Orthodox Church. So, he moved his trips to Ukraine. In late October 2002, my wife Ann and I joined David, her brother Bill Mayhew, and our friends Dr. Tom Stone and his wife Nancy Stone on a mission trip. There were about 5-6 others on the trip. We were to serve as a medical mission to the gypsy people in the western part of Ukraine. We flew from Detroit to Amsterdam and then on to Budapest, Hungary. We spent a night in a hotel and the next morning were picked up by a Ukrainian guide in a large van. He said that he was an ex-tourist guide, but he acted more like ex-KGB. We drove up to the Ukrainian border where cars and trucks were backed up for miles. We passed them all right to the border. Our “Guide” got out with all our passports. He passed a few bottles of homemade wine to the border guards and we were waved into Ukraine. Our home was to be in a hotel in Mukachevo that once housed the Russian Olympic bobsled team. It was rundown from its glory days. We had no hot water and the weather was cold and rainy. “Heat Day” was traditionally on Nov. 1st for all government owned buildings, but due to the government’s austerity program, it was moved to Nov. 15th. After one week, we offered to pay for some hot water. Everyone got a hot shower, and being a gentleman, I waited until the last. While in the shower and soaped up, they turned off all the water on me. I had to sponge the soap off with cold water in a bucket. We had old bunk beds and just a few blankets. We wore several layers of clothing to bed. We found one small radiator and shared it on alternate nights to take off the chill. We were followed wherever we went by two men in leather coats chain smoking cigarettes. We held several clinics for the Roma (gypsy) population. Under the Soviet Union, many Russian people moved into Ukraine and were the favored population. When the USSR broke up, the Ukrainian people took over most government positions and represented 60-70% of the population. The Russian people (30%) were now a minority, but were 1-2 generations removed from Mother Russia. They had to stay in Ukraine. The Roma people were a traditionally itinerant ethnic group before the WWII, but under the USSR, they had to stay in whatever area they were in when the war ended. They had few rights and were very poor, picking up what little work was left over. Essentially, they were camping in makeshift structures at the end of the road. In the clinic, we offered whatever basic care we could provide. Before we left the USA, Ann had many people donate basic reading glasses or what they could buy at Walmart. She was our ophthalmologist and would sit with the Roma ladies and try one pair after another until they could read their bibles. They would hug her and cry. She was a great success. The model of care for disabled children through eastern Europe was to place the children in a state-run orphanage and forget about them. In Mukachevo, we ran into several women who refused to give up their children to the state. They all had to work, so they took over an abandoned house and were fixing it up as a daycare center. When they found out that Bill was an early childhood specialist, he began seeing individual children with Nancy Stone’s help. She was an elementary school teacher. Soon the line was out the door and down the block as women lined up with their children to get Bill and Nancy’s evaluation. They did more good than the rest of us with our attempts at basic medical care. Tom Stone and I decided to visit the local hospital. We were befriended by the two urologists on the staff. They had few resources. If you needed antibiotics, your family had to go out on the market and find them. They had no x-ray film, but they could take an x-ray if you found the film. They had one ultrasound machine for the entire hospital. We made rounds with the physicians, but they never let us get into the OR. I think they were embarrassed. We talked to one woman who knew some English. We asked her why she was in. She explained that she had a kidney cancer 10 years earlier, and was in for a week for her annual checkup. Obviously, they were padding their hospital census to keep their state allotments. We saw few people who needed to be in the hospital. A nationalized healthcare system is only as good as the government funding to support it. For medical care, education, the police and other public services, there were no tax revenues going up to Kiev, and there was no trickle down of money for these services. The teachers had not been paid in three months, the police were never paid and stopped people at random and threatened arrest. Our van was pulled over twice, but we got off as missionaries. Our Urology friends earned about $100/month. Our Urology friends offered to take us out to eat, where we had a very good BBQ rib meal. Then they offered us a vodka toast to our health. We returned the toast and soon we were toasting our countries, our parents, our children, our flags, etc. The vodka must have been watered down as we all walked back to our hotel. Another woman Urologist joined us for the meal. Ann asked her why she was a urologist and she answered, “I love men!” She was also much better off than the men. She had a private practice which we found unusual until we found out that she ran a private venereal disease clinic that was visited by all the government officials, so that nothing showed up on their official health records. We visited the public markets and bought carved spoons sold by the Roma women. We went to the large GUM Department store. It was really just a large building with many private stalls, a marketplace. Ann found a full-length leather coat that would probably cost $800-1,000 in the US. It was priced at $200. We asked David if we would be the ugly Americans if she bought it. He said no, but we only had a few Ukrainian hryvnia. Ann offered to pay in US$ and the salesladies began laughing and crying and hugging. We guessed that the exchange rate was very good for them. David had made arrangements to have a well dug in the gypsy village, so the women would not have to walk through the snow to the stream for water. After we left, a well was dug, but the pump that was used leaked oil and the well was unusable. On our way home, we spent an extra day in Budapest. Although only 10 years separated the Hungarians from the USSR, they had a booming economy, the shops were filled and the people well dressed. There were a lot of automobiles and the people would even smile. A stark difference across borders. Ukraine II - 2004 Tom Stone and I decided that we wanted to return to understand more about the urology care in the country. We returned with just David in the winter of 2003-4. We carried some sample medications with us. This time we stayed in a hotel which turned out to be owned by the Italian mafia. We saw a guard with a gun sitting in the hallway across from our room. The “don” was in town. This time, the room was so hot that we had to open the window at night. We had plenty of hot water. In a socialized system, there are the haves and the have nots. We spent more time with our urologist friends. We only saw their name written in Cyrillic and have forgotten how they were pronounced. We learned that they were totally dependent on the hospital ultrasonographer for diagnosis, and with no hard copy of what he saw, they could never question his diagnosis. In addition, the other services seemed to get the best service. So, we decided that we would get the urology service an ultrasound machine. We travelled to Uzhhorod, the site of a university and the regional medical center. We made rounds and went to lunch. We were made honorary members of the Transcarpathian Urology Society. We travelled in our friend’s Lada car. The four of us were wedged in, and with our weight, it was terribly underpowered. We once pulled out to pass a truck and couldn’t make it and had to pull back in. One memorable experience occurred when we were shopping for a new printer. The daycare center had their computer and printer stolen. They were able to get a computer, but they needed a printer to copy educational and art programs for the kids. Tom and I bought them a printer, and while in the store, a lady approached us because we were speaking English. She explained that she was privately tutoring ten students and she had never been out of Ukraine. The students had never heard a native English speaker. We asked our interpreter if it was okay and then followed the lady out of the store, down an alley, up a fire escape to a small second-floor room. We had agreed to speak to the kids for 15 minutes and ended up spending over four hours. There were the quiet types who were speaking pretty well, and the aggressive types who needed a lot of help. But, they were good kids whose parents were giving them a real economic opportunity if they could learn to speak English. I remember they had a newspaper with a typical real estate ad. It showed a brick ranch-style house and a nice green lawn. They asked, “Is this how you live in the US?” We said that it was typical middle-class housing. They then asked, “Why do you have all of that grass?” We paused to realize that every inch of land around every house in town was devoted to a victory garden growing vegetables or a vineyard. No grass to cut isn’t a bad way to go. David was off in Kiev most of the time, but met up with us for the return trip. Once again, we headed back to Budapest, but stopped first in the Tokaj wine region. The wine is famous because the grapes become covered with a gray fungus just before picking and it produces a lovely sweet wine. The vineyard we visited keeps their wine in a cave and we went down multiple levels. The casks kept getting older and the wine more expensive. The vintner would uncork a huge cask, place a long hollow glass tube into the cask and then trickle a small amount of wine into our mouth. We had lots of tastes and almost had to carry Rev. Behling home. On our return to the US, we asked around at various hospitals and found an ultrasound that Hackley Hospital in Muskegon was willing to donate. We took it to International Aid in Spring Lake, Michigan. They reconditioned the unit and changed the power supply to make it compatible with the 220-volt current in Ukraine. They even found an instruction manual in the Ukrainian language in the Cyrillic alphabet. They crated it up for shipping. It weighed close to 600 pounds. International Aid said that we would have to fly the unit to Kiev and that if we shipped it by boat and truck, it would be “lost.” We told the Urologist to get ready and we would let him know when it got to the airport in Kiev. He rented a large truck and drove 250 miles to Kiev only to be told that the paperwork was wrong. They would only release the unit if we sent a letter stating the US machine was for humanitarian purposes and a second letter apologizing for not sending the HP letter in the first place. We did so even though International Aid said the HP letter was with the shipment. The government in Kiev was just playing games with us. Our friend went a second time to Kiev and returned to Mukachevo with the unit. The US machine was then impounded by the mayor who was the CEO of the Mukachevo City Hospital. The mayor was having an argument with the CEO of the Uzhhorod Hospital who wanted the US machine shipped to him. Somehow, the argument was resolved and the US machine was placed in the Urology area. They had renovated a whole room for its use. One of the urologist’s wives, also a physician, had taken a course in Ultrasound and became the ultrasonographer for the unit. It took us almost six months, but it made us feel good that we had helped our new friends in Transcarpathia. In memory of John W. Hall, MD - his memory is a blessing.

0 Comments

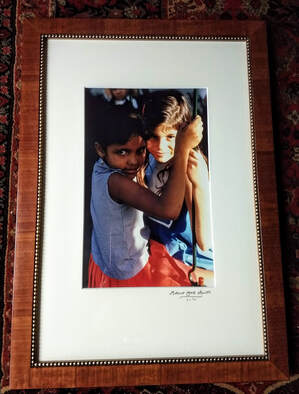

My father would have been 90 today. Here's what he taught me about collecting the beauty in the world. My father was a collector whose precious objects brought him great joy. On this, the day he would have been 90, I am full of memories of what he taught me. He's been gone more than four years now, but my husband and I live surrounded by some of those precious objects: Books, records, masks, pottery, and drums. I have his photo collection in my basement. It's massive. Like Dad, I'm a "Look at the Moon!" person. I'm a "Look at that hawk!" person. I'm a "Look how green the leaves are" person. I'm a photographer who captures and preserves my experiences so I can study them again later, relishing the memories. I love making photos for other people and seeing them in print as lasting keepsakes. I am most passionate about photographing people and showcasing their uniqueness. He was a cultural anthropologist, so his favorite subject was also people. The contrast between my parents and their affinity for things was stark and amusing. My mother didn't even think about material objects (except as tools to do or make), and my father was a passionate, organized, and diligent collector. When he and my mother moved in together, she had a mat to sleep on, two suitcases and two rattan chairs. He brought boxes of his records, books, artifacts, stamps, cameras and photographs. Everything was cataloged and ordered just so. Mom came to treasure his things and share his passion for the artifacts they collected together. My own passion for not just photographs and photography, but also books, stories, music, and adventures, began at his side. Dad taught me about collecting stamps, filled our house with his favorite music, took us on adventurous sabbaticals to Mexico, Guatemala, and Trinidad, and always made beautiful, vivid photos of the people he met and studied. People always react with shock when I tell them I wasn't allowed to touch his cameras growing up. But they were so complicated: his Rolleiflex and light meter still baffle me. I didn't really start making my own photos until I was married and had a camera of my own. I don't look back on his possessiveness as a bad thing, but with a wry, sneaky satisfaction. Why? Because he WANTED me to share his passions, he just didn't want anything damaged. What I did was sneak! I studied his art books. I loved the weight of his giant volumes of great works on my lap. I read Catch 22 and the Planet of the Apes when he left them sitting around (before I was old enough). I "stole" his Bizet Symphony #1 in C Major by taking it to my room and playing it over and over again on my record player. And when I left for college, I took it with me. I studied his photo albums. I went into the field with him when he was interviewing people for his research, and I was so proud to be his daughter when people said, "Robby's here!" The photos he captured of those people had love in their eyes for him. Surprisingly, for all his talent, he was very modest and didn't look for attention from his photography. When I asked him if I could make a print from the slide of this photo, he was baffled. And then I wanted him to sign it, so I could frame it for my house. He complied, reluctantly. He didn't see himself as an artist. I feel this photo captured how I felt around the beauties I met on our travels: I was so pale and big (though not for an American), and my friends and "cousins" were delicate, dark, and beautiful. I wanted to look like them. He captured our friendship and our contrast magnificently in this photograph. I appreciate the legacy our dear old Dad left us. Today, he would have been 90. If he were here, he'd be sad it was sleeting and snowing. His birthday was usually during Passover, so he would have loved the Manischewitz cake we used to bake for him. He would have celebrated seeing forsythia blooming in his yard. And he would have had his camera out to capture all of it. Happy Birthday, Dad. Your memory is a blessing to all of us who knew and loved you. I feel an obligation to my younger sisters to point out that I was an only child until I was six years old. So my experience, my sliver in time with our parents is when they were younger, starting out, and I had their full attention. Before our family was complete with my two sisters, I was lonely for companions, so I had lots of solitary time to look at all of Dad's stuff. My vision for this portrait project has been to create a collection showcasing my bandmates in the Novi Concert Band with one significant portrait of each musician, each with their own unique persona, to share their stories. Why? Because in our society, we are most accustomed to seeing artful photos of our rock stars, athletes, and Hollywood actors. This project is about shifting paradigms and checking assumptions. Making this collection of photographs created an opportunity to portray adult musicians in a fresh light. By working one-on-one with each musician, I’ve been able to share their personal stories, hobbies and passions. The takeaway I didn't expect was the richly diverse collection of experiences we shared in making the portraits. I feel very lucky to have had the opportunity to spend time with each of these interesting people. To stand in the rain and deep freeze, and sweat, and get up too early, haul equipment, tromp through the woods, and knock on strangers' doors for permission to photograph on their property. A few of my bandmates actually took inspiration from what we were doing and got lighting equipment, too. I can't wait to see the photos they make! Someone asked me at the end of making these 50 portraits which one is my favorite. I can't answer that! Each one is my favorite for its own reason. I hope I've been able to convey the fun and adventures we shared. Sometimes I love a portrait for the serious or intense expression captured. Sometimes it's because of the absolute thrill of seeing what would be ordinary on a cellphone snapshot turn into something special by popping my lights and umbrellas. Those portraits that I was able to make match my imagination through post-production editing make me very happy, like flutist Greg floating in the air as his daughters tossed music in the air. Some are my favorites because of the amazing hobbies and collections they shared. A few of these experiences made my heart sing. Standing in the park waiting for trombonist Dan Patient to arrive, I heard and felt the rumble of his motorcycle coming down the road and realized he was bringing it out for me to photograph it! Learning from flutist Amy that having her portrait made left her feeling wonderful about the experience, especially because of the connection I made with her young daughter. That is a precious memory, because helping my subject feel beautiful is always my goal. I thought my own portrait would be the last one in the project, but had the good luck to fulfill one of my first visions for the project a few days before the show went up. One our band members has been struggling with health set backs the past few years, and I had photographed him in concert dress. But I wanted the bari sax playing farmer in his cornfield. He's feeling better these days, so we made a last minute date to make that happen. Driving out to Don's farm with him and seeing not only how he tended 220 acres on his pristine farm until he was 89, but also how the neighbors and their kids love him so was so special You can see I'm very fond of my bandmates. All are favorites for one reason or another. For me, the challenge and goal of embarking on this project was about mastery of the environmental portrait. There are those who say you can never achieve mastery in photography. But for me, mastery means I learned from 50 very different individuals how to work with them to showcase each one of them at their best. Making portraits is not just about the photographer's eye and taste. It's about making an image that makes your subject feel good. Posing for portraits is not a normal act for most adults and not for us as musicians. We like to be in a group, in the background, or not photographed at all! So many negative voices are shouting inside our heads: ""But...my hair, my wrinkles, my belly - my goodness I'm old."" As important as making the click to capture these portraits were the connections we forged. I do not know yet what my next project will be, but I guarantee you that for the rest of my life, the experiences and learning that took place while photographing my bandmates will continue to inform my choices as a photographer. I leave you with this. A challenge like this one I set for myself:

The show is still on display for two more weeks, we have our "Pictures at an Exhibition" concert on Sunday, October 20 at the Novi Civic Center, So please, come out and meet my wonderful bandmates. Here's what it feels like to be two weeks from a public reveal. Another reveal of some of my bandmates from the Musicians' Portrait Sessions was published in Novi Today magazine this week. I've planned for this event so carefully, from coordinating 50+ photo sessions, to selecting just the right portrait to represent each at their best, to collecting their musicians' stories. I have a plan for how to hang the show, the photos are framed and ready to go, but what I didn't have a plan for was early release! I never cheat by skipping to the end of a novel to read the ending before it's time. I didn't know the sex of my baby until she was born. So letting some of the secret/surprise out ahead of October 1 was very hard for me to do.

Someone asked me recently which of the portraits is my favorite. I can't answer that, because each is a favorite in its own way for either the resulting photo, or for the experience we shared in making the photograph, or for the musician's personal story and significance to them of the setting or items in the photo. Each gave me a creative thrill in its own way. These four portraits, released early for Novi Today magazine, are here because three of them are in favorite, perhaps surprisingly lesser-known Novi locations. The fourth was significant. Vietnam veteran, trumpet player, Dan had played taps for soldiers' funerals in the late 1960s. Wearing his Army jacket and boots, and Tet Offensive hat, he stood in front of his division's Huey helicopter 50 years later and played taps for us on Memorial Day weekend. With each portrait, there is a story of the musician in their setting, but also the story of us making the photograph. The thrill I felt when I heard the motorcycle rumbling toward me, knowing he'd polished it up for my session with him, was just as emotional as listening to our veteran play taps. There are many more stories. Looking forward to the real reveal in the Novi Civic Center atrium gallery in two weeks. On display throughout October 2019 in the Novi Civic Center Atrium gallery. Art show opening Friday, October 4, 7-8:30 pm. Concert featuring music on the theme Pictures at an Exhibition will be Sunday, October 20 at 2 pm at the Novi Civic Center with intermission in the art exhibit. Come out and meet the musicians and learn more about their unique stories. Photography by Stephanie Smith Hall, www.WordSmithPhoto.com. Answering the Yearning to Create through a Personal (Mastery) Project - 5 Things I've Learned8/4/2019  Prelude: I spent more than two years immersed in an excellent new photography certificate program created by a team of wonderful Detroit-area photographers. During that time, I learned how to use all the features of my camera, how to incorporate modern photography gear like off-camera lighting into my photos, how to make all kinds of photos in response to teacher assignments and teacher-driven locations. I stretched myself into realms I'd never considered like macro and color for color's sake. The whole time I was learning and practicing for class I was asking myself: "How am I going to define myself as a photographer? What is my niche? What is my style? Who am I as a photographer?” Then, I had an a-ha! moment. I saw a photo of a young tuba player dressed in a suit, leaning casually, but with attitude in an old hallway. I loved it. He looked like a rock star. Showing a concert band musician looking cool is not very common. I’ve always hated that we’re considered geeks or nerds, because I’m one of them and I know how cool they are beyond their white band polos and concert black. My personal mastery project was born as that fully formed idea. I launched into creating a portrait collection of adult musicians with whom I play in a community concert band. Not just a few, but a collection. When the project is complete in October 2019, I will have taken about 50 portraits of adult musicians ranging in age from late 20s to 90. This process has also been about defining who I am as a photographer. Here's what I'm sure of now: I'm looking for exciting gigs with interesting people. I'm looking to make a connection, seal a memory, and create a small, but significant collection or one memorable portrait. I do not know yet what my next project will be, but I guarantee you that for the rest of my life, the experiences and learning that took place while photographing my bandmates will continue to inform my choices as a photographer. Here are five things I've experienced and learned from this project: 1. Hold onto your joy. This is a mantra I say to myself frequently. Like a carefully nurtured seedling, I cautiously, but excitedly shared peeks into my concept with my family, photography advisor, band's directors and a few of my bandmates. Although these trial balloons were well received, I felt the need to hold back on talking about it with them. I wanted to maintain my passion for the project through to completion. I also didn’t want them to burn out on hearing me talk about it too much. 2. There will be resistance. It's your dream, not theirs! Most of my subjects have been very enthusiastic about the project, coming up with a concept, and posing for me. It’s been so much fun, and I feel their commitment to the project through their participation. But there are a few who have questioned why they have to do this. My wise husband had to point that out to me. He said, “It's your project, why should they care?” Well, the idea is they each get a professional, carefully composed portrait of themselves. Additionally, the collection and the musicians’ stories that accompany each portrait will give us 50 stories to tell as a public relations and social media campaign in the coming years: “Meet the Musicians of the Novi Concert Band.” I accept that not all of them will be willing to go out three separate times to get the shot without pouring rain. Not all of them will be willing to stand out in 6° weather for 20 minutes, drive to Detroit and sweat in the Detroit Public Library, or spend three hours getting just the right shot. And I’ve come up with a few solutions that all involve my "Go With the Flow" mantra:

3. Everyone gets nervous in front of the camera. Even the stunningly beautiful ones. I’ve learned so much from my bandmate/photo subjects on this project. It's so important for me to communicate with them about what we’re going for. It always takes a while to relax and the best pictures will be at the end. Yes, it can take about 300 photos to get ‘The One.’ I’ve learned that a little wine can erase a furrowed brow and unsure, questioning gaze. Most importantly, making portraits is not just about the photographer's eye and taste. It's about making an image that makes your subject feel good. Posing for portraits is not a normal act for most adults and not for us as musicians. We like to be in a group, in the background, or not photographed at all! So many negative voices are shouting inside our heads: "But...my hair, my wrinkles, my belly…my goodness I'm old." As important as making the click to capture these portraits were the connections we forged. With each person, I’ve come away realizing the outcomes depended on developing trust, establishing the session as a collaboration, and making sure I kept my confidence up not to get flustered and be fully aware of the scene to maximize the outcome. I had to balance the creative, right brain activity (where I don't necessarily speak much or in complete sentences) with giving clear direction. Showing my bandmates what the photos look like helps them trust that I’m going for the best possible representation of them – and even better, carefully edited photographs will follow. I’ve been working tethered to my tablet, so they can sometimes see their photos straight out of the camera in real time. They then leave the session knowing we “Got IT.” And I keep the complements, thanks, praise and appreciation flowing, too. 4. It won’t feel like work if you’re passionate about it. I was photographing an old friend and she remarked that I just lit up when she was in front of my camera. The thrill of the capture is what makes a photo shoot a great experience for me. People keep saying, “This project seems like a lot of work.” And I keep replying, “It’s not work to me. It’s exhilarating.” Again, holding onto the joy, I’m making sure it doesn’t become drudgery – each person is unique and the settings and stories they are telling are so fun to explore. 5. Plan for the finale. When I first came up with the idea, it was just to photograph every bandmate. Now I have a plan for closure. One night when I was performing at an art show opening in our city hall, I realized that I might be able to showcase MY photography in an art show, too. So, now, I’ve applied, been accepted, and set a date for a show. In addition to a personal show opening, our band will also perform a concert a few weeks later at which all of them, their families and our audience will be able to see the finished collection. When the show goes up on October 1, 2019, I’ll have photographed, edited, and framed 50+ portraits. You’re invited to the Finale: Part 1: Please join me at the opening of the show on Friday, October 4, 2019 from 7 to 8 pm in the Novi Civic Center Atrium Gallery, 45175 W 10 Mile Rd, Novi, MI 48375. Part 2: Come hear the musicians of the Novi Concert Band perform on Sunday, October 20, 2019 at 2 pm, also at the Novi Civic Center, 45175 W 10 Mile Rd, Novi, MI 48375. Our concert’s theme is perfect: Pictures at an Exhibition, and we’ll be performing the Ravel/Mussorgsky masterpiece, along with other pieces about pictures and photographs. You’ll see the portraits from The Musicians’ Sessions on display in the atrium during intermission and get a chance to meet my bandmates, too.  The experience of working with another creative on a photographic project can result in better work than either envisioned or could have made alone. The photos I've taken with Rachel Keown Burke were created in a collaborative, supportive, reciprocal and energizing environment and I'm proud of what we made together. The first opportunity I had to work with Rachel was in January 2018 when she was directing a disturbing drama, Bug, on Stagecrafter's 2nd Stage. Together we planned the shoot with specific shots, themes, color toning, and moods in mind. When I arrived at the shoot, we moved smoothly from one set up to the next, 1,2,3,4,5. It was the first time I ever worked tethered - a cord from my camera immediately showed the resulting photos on my tablet which Rachel was holding as I took the photos. Together, we were able to see what we were getting and tweaked and critiqued in real-time, and left the session knowing we had succeeded. The photo above is from that shoot and depicts the character Agnes in all her broken, frightened, confused loneliness. A year later, Rachel reached out again for headshots for herself. I have seen her as an actor twice on stage, so I knew there were many expressions I was looking to capture among her compelling range of emotions. Eliciting the depth and breadth of her skill as an actor was my goal. Again, we had a plan to show powerful, centered, fearsome and other expressions. Having such a self-aware actor in front of my lens gave us both so many options to choose from. Her transformation before my eyes was fascinating and thrilling. Making a photography subject happy with their portrait is top priority. But when the process has been creative, collaborative, and supportive, its magic translates into special photographs.  Photo by @JackHoylePhotography Photo by @JackHoylePhotography A common mantra in photography is: "There's no such thing as mastery." Why? Because the skills and tools are forever evolving, and the concept that a photograph has achieved perfection is supposedly always a bit beyond our reach. That leaves every photograph open for ongoing critique and implies it can't just be a wonderful capture of a moment in time as interpreted by the photographer's unique editing eye and vision. I beg to differ. I come from other disciplines where the concept of mastery is a gratifying life challenge. Throughout my adult life I've chosen mastery projects where I set a goal, however lofty, and work until I achieve it. Sometimes, it's harder than I ever imagined it would be, and that makes the finale that much more gratifying. My most recent example is having handmade my daughter's wedding dress. I'm proud, as a seamstress, that I designed it by making my own pattern and the dress was perfect for her. Honestly, the hardest thing about this experience was finding enough time. It took four months of squeezing every minute I could to work on design, fitting, and sewing. The reason I stress that is that I've always said what makes a good seamstress or knitter is the willingness to redo or fix mistakes. Take the time to make it right. Now, I have had a mother's joy of zipping my gorgeous daughter into her dress then sneaking a peek to watch her bridal glow as she showed her dream dress to her groom. I believe it could not have been done without the willingness to invest the time, effort, and commitment to do whatever it takes (working late or early with bleary eyes) to achieve the goal. There's so much more than skill and artistry at play in saying "I made my daughter's wedding dress." This was mastery at the most personal level, and making her dress was the most high-stakes, high-profile project of my life. As a flutist, I've sought mastery in music. I have a few treasured bucket list experiences where I played a concerto or a show that challenged me to push every skill I have to higher levels. I'm a slow learner, so when a piece is presented to me, sometimes I can't even read it, let alone coordinate it into music from the page to my brain, lips, fingers, and flute. But I practice, study, listen, and live with that piece until I know it inside and out, so eventually, or by the performance date, almost magically, it becomes a natural extension of myself. It becomes "my piece." As a teen, I knew I had achieved that level of mastery when I caught my dad whistling my piece while shaving, or sitting in the back of a performance space with his head tilted up while stroking his beard. I know, that's external validation, but I admit it's also important to the creative process. (Confession: I do not practice on a regular basis. I practice when I have a public performance to prepare for.) Not everyone can play the flute or sew a wedding dress, but today, most everyone can make a photo. As I strive to define myself as a photographer, part of the task is separating the creative mastery I aim to achieve from snapshots or mass-produced, trendy uniformity. My goal is to capture special moments, glances, personalities. Just like I've held very closely to my sewing joy by declaring, "I only sew for love," Although I don't only photograph for love, I have found that I get that mastery kind of joy out of it when making a memorable connection with my subject. There are photos in my portfolio I could not have made if I had not invested time on them and made an emotional commitment to establish trust. The best is when my model and I both revel in sharing the creative energy. I am striving to expand my photography experiences while holding onto that joy of being creative, not a technician. I'm always looking for my next mastery project, so I'm accustomed to endeavors that take a lot of time. I like massive projects! When I approach a photography session, I also take my time. This sometimes surprises my subjects. What? You took 300 shots? Why is it taking you so long to select and edit my photos? Last year, when two professional photographers called my work "fine art" photography, I was dumbstruck. But I think that helped me define myself as a photographer - I'm looking for experiences and people who want to participate in achieving mastery with me while in front of my lens. I'll explore this concept more soon as I reveal a personal mastery project I've been working on that has further defined my work as a photographer. |

Blog: Stories from Behind the LensAs much as I revel in the final image and love returning to look at them again and again, the process of making a photo is also a treasured experience. |